14 The Small Town and the Big City

The Small Town and the Big City

The opposition between the “city” and the “country” is one of the oldest tropes in literature. In the 1970s, the British literary theorist Raymond Williams summarized:

On the country has gathered the idea of a natural way of life: of peace, innocence, and simple virtue. On the city has gathered the idea of an achieved centre: of learning, communication, light. Powerful hostile associations have also developed: on the city as a place of noise, worldliness, and ambition; on the country as a place of backwardness, ignorance, limitation. (R. Williams 1)

Even though this is clearly a false opposition, it is still easily available to writers of all kinds. If you’ve ever heard a politician compare “big city types” or “coastal elites” to “the heartland” or “the salt of the earth” (or, more troublingly, “real” Americans), you’ve witnessed the rhetorical power of this opposition. The same goes if you’ve ever seen a romantic comedy about a small-town girl or boy who moves to the city in search of fame and fortune, only to be drawn back home, and so on.

Anderson knew all about the push-and-pull of country life and city life. He grew up Clyde, Ohio, a small town which provided some of the inspiration for Winesburg. After several years of working odd jobs and a failed attempt at living in Chicago, he became president of a mail-order paint factory in Elyria, Ohio. One November day in 1912, he abandoned the business, his wife, and their three children. He moved to Chicago for a second time and joined an artist’s colony. Anderson retold the story of his departure several times over the decades, alternately as a confession of a “nervous breakdown” (his words) and as the self-righteous fable of “an artist’s resistance to the shackles of the business world” (Moore, ch. 3). His frequent complaints about the “shackles” and “stink” of the business world notwithstanding, he worked in advertising until 1922, rising in the ranks from ad-copy writer to senior executive. He kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings with headlines like “An Advertising Man Who Writes Good Fiction” (Olson, Chicago Renaissance). By night, he experienced the city as a site of artistic, intellectual, and sexual freedom. Yet it was to the memory of Clyde and Elyria that he returned in his writing.

Historical context: Read about the Dill Pickle Club, the Chicago bar where Anderson hobnobbed with jazz musicians, radical academics, prostitutes, drag performers, hoboes, and other famous writers; see Quinn Myers’s “Chicago’s Dill Pickle Club: Where Anarchists Mixed With Doctors and Poets.” (This material is optional.)

Anderson is often described as a regional or a Midwestern writer. The label regionalism points to a connection between the geographic setting of a writer’s work and the style or themes of their writing. In the case of Winesburg, Ohio, we see on one hand, a Realist’s grounding in concrete places and day-to-day life, and on the other, a tendency toward symbolic uses of the setting.

As Mark Buechsel writes:

[T]he term ‘Midwest’ became associated with the American pastoral myth in the late nineteenth century and ended up designating those agriculturally productive, famously fertile north-central states that were perceived as ‘pastoral’ places, realizing Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a great American garden in which independent family farmers live dignified, happy lives, providing for their households’ needs abundantly by cultivating the rich and rewarding soil, leading lives free from care, and being preserved in virtuous character through honest labour…. Thus, the interaction of the nineteenth century’s increasingly industrial civilization with a fertile region full of mythical pastoral promise is the central experience defining the region’s identity. (Buechsel 11–12)

The word pastoral comes from the same root as pasture. As a literary mode, it originated in classical Greece and Rome. Pastoral poetry elevated the lives of pre-industrial farmers and shepherds to the status of “Arcadia,” heaven on earth. All the people in pastorals enjoyed modest possessions, harmless flirtation, strong communal ties, and the reassuring seasonal cycles of growth, harvest, death, and renewal. The pastoral mode saw a revival in seventeenth-century England, with poems such as Christopher Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” (1600), Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” (published 1681), and Oliver Goldsmith’s “The Deserted Village” (1770). These revivals were shot through with nostalgia for simpler times, against a backdrop of political and social unrest. Subsequent literary movements were highly critical of pastoral. We have seen Realism’s preference for complex characters over types and Naturalism’s brutal depiction of labour. Realist, Naturalist, and Modernist writers saw the modern world as fundamentally different from that which came before, rejecting the ahistorical cycles of the pastoral. And writers increasingly saw the city as the locus of social life. This was borne out by demographic trends: The 1910s was the first decade during which more Americans lived in cities than in rural areas (Newcomb). Winesburg, Ohio is set in the 1890s, at an earlier stage of this transition.

Anderson’s strong sense of place informed the structure of his best known work. The genre of Winesburg, Ohio is now known as a short story cycle. We can think of a short story cycle as a cross between a novel and a collection of short stories. The short story cycle was a perfect marriage of regionalist and Modernist impulses (Smith). Michael Levenson, discussing Winesburg’s significance for the development of Modernist literature (and its subsequent importance to Hemingway), explains further:

The volume offers reappearing characters…and recurrent locations, but the continuity is perpetually broken. New situations begin again in each story; central conflicts remain inconclusive; in place of resolution stands a next problem for a next story. The town, Anderson’s fictional Winesburg, gives a unity of scene, insistently exposed as a false unity. Individuals collide without meeting; they perform their lives within the terms of private will and personal obsession; they constitute an assemblage but never a community. (Levenson 231)

“Unity of scene” is a reference to Aristotle’s Poetics. It refers to the expectation that the actions in a dramatic work take place in the same setting.

Sherwood Anderson wrote in his first autobiography, A Story Teller’s Story (1924):

There was a notion that ran through all story telling in America, that stories must be built about a plot and that absurd Anglo-Saxon notion that they must point a moral, uplift the people, make better citizens, etc., etc. The magazines were filled with these plot stories, and most of the plays on our stage were plot plays. ‘The Poison Plot’ I called it in conversation with my friends as the plot notion did seem to poison all story telling. What was wanted was form, not plot, an altogether more elusive and difficult thing to come at. (quoted in Scofield 128)

While this may have been unfair to “all story telling in America,” Anderson’s exaggerated revolt against custom is a typical Modernist statement. There is the conviction that writing should be valued for its own sake, not as a means toward an end (compare Gilman), and the embrace of the “elusive and difficult” (compare Norris). “Form” is one of the most common yet vaguely defined terms in literary studies. It is sometimes used interchangeably with genre or technique; other times, it is used as the antithesis of content, to refer to the aspects of a work that cannot be easily summarized. Neither of these descriptions is entirely adequate to Winesburg. As Levenson’s description above shows, the form of Winesburg cannot be fully separated from its content. The organization of the tales within the collection reflects the social organization—really, social dissolution—of the town. Anderson achieves meaning through the repetition and juxtaposition of motifs. We meet a “tall dark girl” in “Paper Pills,” and again in “Mother”; that we recognize her as the same woman is relatively unimportant. Incidents in characters’ lives are presented out of order, asking us to suspend our desire for a definitive record of causes and effects. Anderson’s preference for spatial over temporal organization shows the influence of painting and sculpture on his work, which you will read about shortly.

Anderson’s animosity toward plot was not as pronounced as Gertrude Stein’s. In spite of its non-linear structure, Winesburg is recognizable as a Bildungsroman (German for ‘novel of formation’ or ‘novel of education’: in short, a coming-of-age novel), a mode which has roots going back to the eighteenth century. More specifically, Winesburg can be characterized as a

Künstlerroman (‘novel of the artist’), which explores incidents in the creative development of an artist or a writer. George Willard is clearly the artist in this case, but he is not always the centre of attention. Jennifer Smith writes:

Although George figures as a central organising figure in Winesburg, the cycle complicates his primacy through the emphasis on surrogate characters. The stories obscure the distinction between major and minor characters by having the latter function as protagonists in individual stories. For instance, Helen White, Enoch Robinson, and Seth Richmond are the protagonists of their own stories, and they often explicitly comment on why George has been singled out over them. While George appears to be a powerful unifying force, Anderson displaces some of his centrality onto the populace, questioning the possibility for textual and symbolic unity through an individual. The stories critique the aggrandisement of a single individual and challenge the overt nostalgia often aligned with George. The sheer multiplicity of such alternatives intimates that this glorification is often arbitrary and violently minimises the potential of other promising figures, many of whom are artists (for instance, Enoch paints). (Smith 28–29)

In the next sections, we will consider Anderson’s beliefs about artistic creation and the character of the artist.

Before continuing, read “The Book of the Grotesque” (the preface to Winesburg, Ohio).

“The Book of the Grotesque”

Grotesque is a representation of a character “where normal features and/or behaviours are manifested by distortions expressed in extremes that are meant to be frightening and/or disturbingly comic. These characters may induce both disgust and empathy” (“Literary Glossary”). The word originates from the Italian grotto (‘cave’), suggesting something that crawled out of hiding. Grotesque figures were a staple of literature from the Romantic era: for instance, Frankenstein’s creature, the Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Captain Ahab from Moby-Dick.

“The Book of the Grotesque” was Anderson’s working title for the collection of stories that became Winesburg, Ohio (Ritzenberg). Even with the title changed, it is not difficult to recognize that the collection we hold is the writer’s book. But what else does the preface suggest about what is to follow? If the writer’s book was never published, why are we reading it? What is the relation between the writer and “I,” the storyteller who interprets both book and writer for us? For that matter, who are “you”? From the beginning of the preface, we can see Anderson’s technique of description via synecdoche, using a part to represent the whole. We know the writer by his white moustache and the carpenter by his mouth. We also learn that the writer is “like a pregnant woman.” Compounding the figures of gender inversion, the writer is pregnant with a woman who is wearing the “mail” (a possible pun on ‘male’) costume of a knight (Nagy 782).

Male pregnancy is, in fact, an old trope in European literature and philosophy. As Michael Davidson explains:

Plato in Theaetetus [ca. 369 BCE] speaks of ‘philosophical pregnancy’ in which the corporeal pregnancy of women is contrasted to the philosophical travail enabled by Socrates…. As Sherry Velasco points out, the image of male pregnancy appears in numerous medieval and early modern works by Cervantes, Giovanni Boccaccio, Shakespeare, and John Dryden. In such early narratives the figure of male pregnancy rearticulates biological reproduction by positing epistemological or aesthetic creativity against female conception, gestation, and birth (in his prologue to Don Quixote [1605–1615], Cervantes describes his book as ‘the child of my brain’). (Davidson 210)

The figure of the male-creator-as-pregnant-man mostly vanished after the seventeenth century, a consequence both of the ascendance of realism and modern anatomical science. On the rare occasion when a pregnant man did appear, it was, yes, grotesque, a symbol of sexual perversion and decadence. But that is not how Anderson is using the figure. Here, it is the “young thing inside” the writer that “saves” the writer from becoming grotesque. This androgynous being inside the writer represented something that Anderson believed was vanishing from modern life. In 1925, he wrote: “Although in America and during the long period which we have all been so busy conquering the mechanical world we have in general looked upon the poet or the artist as rather a sissy, a nut, a man who had better be brushed aside, we all have something of the poet and lover in us” (quoted in Kahan 89). In short, the pregnant

storyteller encapsulates two critiques of American modernity: one, the loss of craftsmanship brought about by mass production; two, a loss of androgyny (or perhaps the sequestering of androgyny into a modern concept of homosexuality).

So what is Anderson’s grotesque? The grotesque is a social outcast; he or she may be a victim of cruelty, or a perpetrator of it. The grotesque is that which “cannot be standardized,” and which is therefore portrayed with nostalgic fondness (Kahan 93–94). The grotesque is contorted in pain which he or she cannot express. The grotesque clings to outmoded or dogmatic personal truths. And, as we will see in the next section, the grotesque was closely linked to Anderson’s literary style.

The Grotesque and Expressionism

Before continuing, read “Hands,” “Paper Pills,” and “Mother” (the first three tales of Winesburg, Ohio) and “Anderson’s Expressionist Art” by David Stouck. Whether you choose to read the stories or the critical article first is up to you.

As you read David Stouck’s discussions of Expressionist painters, you may wish to browse the Guggenheim Museum’s “Expressionism” collection online. Make sure you understand the

following:

- The characteristics of Expressionism in the visual arts and in literature

- Why Stouck considers Expressionism a Weltanschauung (worldview), not just an artistic style

- Why Expressionism is not an absolute break from Realism

- Stein’s influence on Anderson (examine the comparison of Anderson’s early prose to “Paper Pills” in section II)

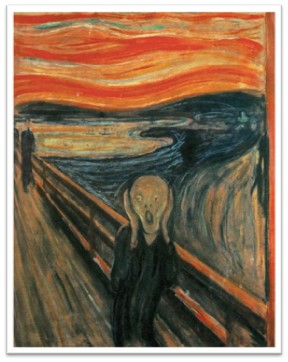

Stouck implicitly compares Winesburg, Ohio to Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s The Scream. Do you think this is an apt comparison? Why or why not? For more examples of the grotesque tendency in Expressionist portraiture, see MoMALearning’s webpage “Expressionism.”