18 The Question of Communism

What did it mean to be a communist in America before the Cold War? Here are some of the social policies they advocated:

- All workers being able to afford food, clothing, and shelter

- Weekends, bathroom breaks, and going home for the holidays

- Safety protections for workers (remember Trina McTeague?)

- Making education free and eliminating child labour

- Providing the same protections to workers regardless of their race, ethnicity, or gender

One does not have to be a communist to support those policies, but many of the people on the front line of the labour movement in the early twentieth century were communists or socialists. What differentiated communists from progressive-era liberals was that they also subscribed to the tenets of Marxist philosophy. We have only listed a few of these tenets, in a simplified form. Students wishing for a more rigorous survey of Marxist theory may visit Purdue’s Introduction to Marxism page.

- Class struggle as the driving force behind human history. Marx distinguished between those who owned wealth-generating property (the bourgeoisie) and those who do not (the proletariat, which literally means “without property”). When Bigger realizes that Henry Dalton, who “gave millions of dollars for Negro education,” only rented his smallest, dirtiest rooms to black families, he decides to send the ransom letter to “jar them out of their senses” (Native Son, Book 2).

- The alienation experienced by workers who are unable to enjoy the fruits of their labour or make meaningful decisions about their lives. Recall this description of Bessie from Book 2: “He had heard her complain about how hard the white folks worked her; she had told him over and over again that she lived their lives when she was working in their homes, not her own. That was why, she told him, she drank” (Native Son, Book 2).

- Laws, religion, and many of the customs of daily life as an ideology that upholds the interests of the ruling class. Bigger observes that “Bread sold here [in Chicago’s Black Belt] for five cents a loaf, but across the ‘line’ where white folks lived, it sold for four” (Native Son, Book 2). He knows the “line” has no physical substance, but he also knows he cannot cross it. Additionally, there is no intrinsic connection between the use value of the bread and its exchange value. Here you might recall our discussion of the value of gold in McTeague. The necessity of revolution: Communists did not believe that these problems could be overcome by making incremental changes to the existing system (with the introduction of minimum wage laws in the 1920s and 1930s, for example), nor by running away from it (say, to Herland). The only viable course of action was to abolish capitalism entirely.

Individuals who supported the labour movement but did not join a revolutionary party were sometimes referred to as “fellow travellers.” Boris Max likely falls into this category.

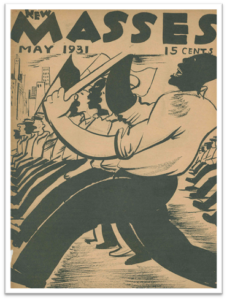

Wright discovered Communism in the early 1930s and began contributing to a variety of left-wing publications. In the defining statement of the early part of his career, he wrote:

It is through a Marxist conception of reality and society that the maximum degree of freedom in thought and feeling can be gained for the Negro writer. Further, this dramatic Marxist vision, when consciously grasped, endows the writer with a sense of dignity which no other vision can give. Ultimately, it restores to the writer his lost heritage, that is, his role as a creator of the world in which he lives, and as a creator of himself. (“Blueprint for Negro Writing” 102)

Whether Marxism actually grants that much power to the individual is questionable. One hears in these lines an anticipation of the Existentialist philosophy that Wright turned to in the mid 1940s.

For an overview of Existentialism, watch CrashCourse’s “Existentialism: Crash Course Philosophy #16” on YouTube.

“Existentialism: Crash Course philosophy #16.” YouTube, uploaded by CrashCourse, 6 June 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YaDvRdLMkHs.

But wait, you might be thinking. If Wright was a committed Marxist, why is the only self-declared communist in the novel, Jan Erlone, a figure of ambivalence at best? Wright often found himself in conflict with members of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), eventually leaving the Party in 1942. As Wright’s biographer Michael Fabre explains, “the socialism practiced by the American Communist Party did not give enough attention to the fight against racism and the development of the individual” (quoted in Ahad 86). Take note of how those two tensions—between the workers’ struggle and the black struggle, and between class analysis and psychological excavation—play out in Native Son.

In a 1940 review of Native Son, the Communist Party coordinator for New York called the novel a “terrific indictment of capitalist America,” but declared Max’s abandonment of Bigger un-Marxist (quoted in Afflerbach 97). Max, that critic implied, had given up. Other Communist Party members criticized Native Son for its “nationalist racial spirit,” even though Wright himself rejected black nationalism (Maxwell, New Negro, Old Left; Dawahare). From an orthodox Marxist perspective, race was an ideologically smokescreen for class divisions; by focusing on the conflicts between black and white Americans, Wright could be said to be turning members of the working class against one another. How would you respond to either of those critics’ arguments?

Wright and the FBI

During the 1930s, when Native Son was set, America’s “Red Scare” was only beginning. It rose to a fever pitch in subsequent decades, resulting in the persecution of many black writers and Civil Rights leaders.

J. Edgar Hoover, the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), saw it as his duty to keep an eye on the literary scene. He hired special agents as “ghostreaders” to scan novels, poems, and plays for hints of obscenity or subversion. Works by African American and left-wing writers came under special scrutiny. In 1942, Hoover directed the FBI to examine all of Wright’s published writing, along with his “background, inclinations, and current activities” (quoted in Maxwell, F.B. Eyes 215).

By 1949, Wright had grown so tired of “G-Men” following him around that he wrote a poem about them, “The FB Eye Blues”:

That old FB eye

Tied a bell to my bed stall

Said old FB eye

Tied a bell to my bed stall

Each time I love my baby, gover’ment knows it all. (quoted in Maxwell, F.B. Eyes 216)

Undoubtedly, the “FB eye” had contributed to Wright’s decision to leave the U.S. two years earlier, in 1947. The FBI surveillance of Wright and his contacts continued until 1963, three years after his death.

We mention this part of Wright’s life not to explain any part of Native Son, but to encourage you to ask questions about the ways institutions read literary texts. At the same time that the FBI was trailing Wright, philanthropic organizations and sociologists were promoting “race novels” as a means to teach white Americans about the psychological effects of racism (Melamed). We like the latter approach better, and we suspect you do, too. However, consider this: The FBI feared Wright because they considered his work revolutionary. Liberal sociologists considered his work therapeutic and harmless. In other words, both institutions were engaged in what scholars refer to as “containment” of the text’s radical energy. As Theodore Martin argues, Native Son does not simply offer an explanation of black crime; it poses the threat of black crime as an “insurrection” against a racist, capitalist society.

Optional: View Wright’s now-declassified FBI file