4 Henry James’s In the Cage (1898, Revised 1908)

Henry James’s In the Cage (1898, Revised 1908)

In the Cage is very modern in its preoccupations with the changing roles of women and the power of technology to bring people at once closer and farther apart. It is also formally innovative. Given how close we get to “our young lady,” the telegraphist, it is easy to forget that she is not the narrator of the novella. James is using a narrative technique known as free indirect discourse. The novella is written in the third person, yet still grants us the moment-by-moment access to the character’s mind that we associate with a first-person narrator. In chapter 2, the statement “people didn’t understand her” is not spoken by the main character, but we recognize it as her private feeling. (Technically, In the Cage does have a first-person narrator; watch out for the occasional interjections of an “I.”) Free indirect discourse allows a narrator to present a character’s thoughts without having to endorse those thoughts as true. It’s a fitting narrative strategy for a tale about partial knowledge and self-delusion.

The English setting of the novella is more specific than that of “The Real Thing.” London is fertile ground for an exploration of social classes and customs, as well as the subjective qualities of experience James was increasingly attuned to. He reflected that London seemed to “make its own system of weather and its own optical laws.” It had an atmosphere that made “everything brown, rich, dim, vague,” with the overall effect of “magnif[ying] distances and minimis[ing] details’’ (quoted in Freeman 91). City life granted women and men new freedoms (particularly those stemming from anonymity) along with pronounced feelings of loneliness and alienation. And the ticks and hums of technological modernity could be at once an “expansion of [one’s] consciousness,” and a new way of being bored.

Reading Closely: Chapters 1 and 2

Let’s read chapters 1 and 2 together. Our observations are meant to demonstrate the technique of passage analysis—that is, commenting on word- and sentence-level details. In an exam setting, you would also want to explain how these early chapters foreshadow later developments.

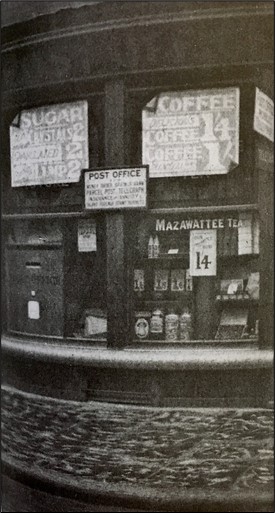

Chapter 1 introduces us to the primary setting, Cocker’s. Note that while there is only a “frail” wooden barrier between the smelly grocery and the post office, the main character perceives a clear “social [and] professional separation” between the telegraphists and the grocers. Do you think the customers see it the same way? Pay attention to the main character’s feelings about being engaged to Mr. Mudge, noting, if you will, that mudge is a portmanteau of mud and sludge. Mayfair, where Cocker’s is located, is a wealthy London neighbourhood; Chalk Farm, where Mr. Mudge runs a shop similar to Cocker’s, is a working-class suburb. Finally, note the way the main character’s family history is introduced:

It would be far from dazzling to exchange Mayfair for Chalk Farm, and it was something of a predicament that he so kept at her; still, it was nothing to the old predicaments, those of the early times of their great misery, her own, her mother’s, and her elder sister’s—the last of whom had succumbed to all but absolute want when, as conscious, incredulous ladies, suddenly bereaved, betrayed, overwhelmed, they had slipped faster and faster down the steep slope at the bottom of which she alone had rebounded. Her mother had never rebounded any more at the bottom than on the way; had only rumbled and grumbled down and down, making, in respect of caps and conversation, no effort whatsoever, and too often, alas! smelling of whisky. (ch. 1)

A more sentimental writer than James could get a whole novel out of a grieving widow’s descent into alcoholism and her daughters’ subsequent poverty. But James compresses it all into two sentences, undercutting the family’s suffering with morbid humour and understatement. (“Caps and conversation” means looking to remarry.) Psychologically, these sentences could be said to illustrate what William James called the “stream of thought,” in which each idea is associated with the next by an emotional association rather than by causality. The chapter ends abruptly, with the instigating question of whether to move to Chalk Farm left unanswered. It is as though the main character has forced her memories to a halt, or James himself has skirted the edge of sentimentality and then “rebounded.”

Chapter 2 gives us an inwardly focused portrait of the telegraphist. The chapter begins with her on a reading break. Note the contrast between the books themselves, which are cheap and “greasy” (she might be reading a book illustrated by the narrator of “The Real Thing”), and the way the telegraphist experiences her reading time, as a “sacred pause” and a means of connection with the wider world. All those books about “fine folks” surely inform the way she “reads” her upper-class customers. Is In the Cage just another tale of a woman led astray by her overactive imagination?

The next two sections, “Telegraphy and the Changing Nature of Women’s Work” and “‘How little she knows! How little she knows!…How much I know!’” provide further historical background to In the Cage, which may be helpful for your understanding of the novel or for developing essay topics. You will not be asked specific questions about historical figures or incidents on the exam.

Complete the learning activities at the end of the topic once you have finished.

Telegraphy and the Changing Nature of Women’s Work

Electrical telegraphy was developed in the 1830s. Initially used for military purposes, telegram services were widely available in the U.S. and Europe by the 1870s. The technology behind the telegraph formed the basis of the radio and the telephone (called a Harmonic Telegraph when it was invented in 1876). Being able to send a message across the country in a matter of minutes transformed the culture’s understanding of distance and time. As the telegraphist in In the Cage reflects, “All the wires in the country seemed to start from the little hole-and-corner where she plied for a livelihood” (In the Cage,ch. 5).

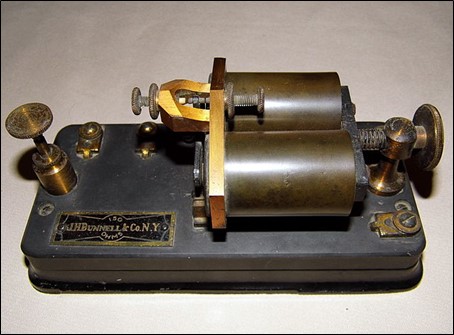

The telegraph also changed the way people thought about language (Hayles; Thurschwell). In order to send a telegram, the message had to be converted to Morse code, where each letter was represented by a sequence of short and long pulses (“dots” and “dashes”), converted into an electric signal, and transmitted over wires. The receiving instrument, called a sounder, converted the electrical pulses to clicks, which an operator would translate into alphabetic letters. The operator had to monitor the sounder at all times for incoming messages, listening intently. Since any interference could corrupt the transmission, the sounder at Cocker’s is kept in “the innermost cell of captivity, a cage within the cage” (ch. 3). No wonder the main character dislikes it!

About a third of the telegraphists in England were women. The job required a sharp memory, the ability to work with delicate equipment, and interpersonal skills, all seen as feminine qualities. Telegraph companies recruited women by promising clean, respectable, “light” work (quoted in Rowe 491). Compared with farm or factory work, it was. Still, a telegraphist could work nine or ten hours a day, six days a week, and her job was often tedious and dehumanizing. James’s operators in the “cage” are compared to animals in a zoo. And the real-life telegraphists of London were embroiled in a fight for fair pay (Moody 55–56). James would not have called himself a feminist, and he had been fairly dismissive toward working women in his earlier novels. In the Cage, however, approaches the telegraphist’s work, ambitions, and frustrations with insight and sympathy.

Since telegraph companies charged customers for each word, long telegrams were a luxury. This is why the narrator speaks drolly of “the class that wired everything, even their expensive feelings.” A fond expression like “much love” did not literally cost as much as “a new pair of boots” (ch. 5; see also Moody), but the medium encouraged people to write in a fragmentary, abrupt style. In this regard, a telegram was the antithesis of the flowery Victorian novel, whose writers were paid by the word. As John Carlos Rowe points out, James’s signature prose style, with its long, windy sentences and psychological subtlety, is starkly different from the clipped style of the telegraph. Yet both writing styles were necessary to capture the

experience of the dawning twentieth century (485–486).

Unlike the text of a letter sent by post, the contents of a telegraph were always known to at least one person other than the sender and the recipient. This is the position in which the protagonist of In the Cage finds herself. By law, postal workers were supposed to maintain the privacy of their clients. The clerks “were never to take no notice, as Mr. Buckton said, whom they served,” but they gossip nonetheless (ch. 3). In addition to the threat of exposure by a disgruntled operator, telegraph wires could be “tapped” by police officers, criminals, or busybodies. If any of this sounds familiar—the sacrifice of privacy for speedy transmission, the trend toward writing in a clipped, economical style, the awareness that one’s intimate conversations relied on a network of wires too complex for any one person to understand—you will understand why historians have described the telegraph system as the “Victorian Internet” (cited in Igo).

“How little she knows!…How much I know!”

A decade before he wrote In the Cage, Henry James complained about “the devouring publicity of life, the extinction of all sense between public and private” (quoted in Igo 17). Although the camera-toting paparazzi that had sparked his ire were a new phenomenon, it was not true that privacy was going extinct. As we mentioned earlier, privacy was a recent invention.

Between 1889 and 1890, the English tabloids were filled with lurid details of the “Cleveland Street Scandal,” when it came to light that a pimp had been arranging meetings between aristocratic men and “telegraph boys” at a brothel in London’s West End. One of James’s close friends, a man named Howard Sturgis, had been among the clients. James also read with fascination and pity about the trial of Oscar Wilde, who was imprisoned in 1895 in connection with an affair with Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, the Marquess of Queensberry. Wilde, like some of the wealthy men implicated in the Cleveland Street Scandal—and like In the Cage’sCaptain Everard—had travelled under a fake name. (If Everard’s nickname “the Pink ‘un’” is sexual

innuendo, as many critics take it to be, it’s an ambiguous ‘un compared with “ever ‘ard.”) As Hugh Stevens remarks, “Whether these echoes are unconscious or not, In the Cage and the Cleveland Street Scandal have shared concerns: prominently, the fact of scandal itself, and an aristocracy compromised by having its private life made public” (129). Even though there is no indication that Everard is gay, blackmail and homosexual activity were closely linked in the nineteenth-century imagination, especially since Queen Victoria had recently made sex between men a crime.

The intrigue of In the Cage comes from asymmetries of knowledge. The main character’s job leaves her feeling at once invisible and exposed, “clever” and “stupid.” She knows when her customers are having a secret rendezvous, but not their real names. She remarks upon the “intense publicity of her profession” (ch. 2), though she is anonymous and forgettable to most

of her visitors. In a culture flush with gossip both innocuous and life-changing, the availability of knowledge and one’s ability to act upon the knowledge were divided along lines of technological skill, gender, and class.