15 Ernest Hemingway’s Great American Boy-Men

Ernest Hemingway’s Great American Boy-Men

Ernest Hemingway was born in 1899, the son of a doctor who was fond of hunting and a vigorous outdoor life. Hemingway inherited his father’s delight in these pursuits, fully embracing the “Roosevelt masculinity” we discussed in our unit on Frank Norris. After serving as an ambulance driver in World War I, Hemingway returned to North America to work as a journalist. He befriended Sherwood Anderson in Chicago. In 1921, Anderson sent Hemingway to Paris with a letter of introduction to give to Gertrude Stein. Hemingway had not yet published a single work of fiction. Hemingway worked as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star (now the Toronto Star) during the Greco-Turkish War and then became an editor of the transatlantic review, a short-lived but influential journal which published experimental fiction, poetry, and highbrow social commentary in English and French.

Learning from Stein and Anderson, Hemingway made directness and conciseness the criteria for effective storytelling. From them he also learned the value of using a simple vocabulary, each word chosen for maximum effect. He could labor for days over a single sentence, and spend weeks recasting a single paragraph. Hemingway’s prose is distinctive and easily recognizable, the object of many parodies and many more sincere imitations.

Caricatures of Hemingway’s style have taken on a life of their own. In 2013, two software developers created the Hemingway App, which promises to “cut the dead weight from your writing” by “highlighting adverbs, passive voice, and dull, complicated words” (.38 Long). But simplicity alone does not make a Hemingway sentence; many passages actually written by Hemingway are scored poorly by the program’s algorithm. In fact, Hemingway’s style is a careful balance of the simple and the complex. Likewise, his dialogue often appears flat on the page, but is in fact contrived, understated, and taut with the rhythms of poetry.

To frame Hemingway as a “high” Modernist—a serious, difficult artist influenced by other serious, difficult artists—is to mischaracterize both Hemingway and Modernism. As the poet Delmore Schwartz observed:

Hemingway’s style is a poetic heightening of various forms of modern colloquial speech—among them, the idiom of the hardboiled reporter, the foreign correspondent, and the sportswriter. It is masculine speech. Its reticence, understatement, and toughness derive from the American masculine ideal, which has a long history going back to the pioneer on the frontier and including the strong silent man of the Hollywood Western. The intense sensitivity to the way in which a European speaks broken English, echoing his own language idioms, may also derive from the speech of the immigrants as well, perhaps, as the special relationship of America to Europe which the fiction of Henry James first portrayed fully. (quoted in Sollors 128)

Hemingway’s literary influences, too, went beyond the Modernist canon. As Susan Beegel points out:

We study [Hemingway’s] indebtedness to sophisticated and esoteric writers such as Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, and T. S. Eliot and largely ignore his indebtedness to popular nature writers such as Rudyard Kipling [the Indian-born British writer known for The Jungle Book], Jack London [whom we met in the unit on Naturalism], and Ernest Seton Thompson [founder of the Boy Scouts of America]. (Beegel, “Eye” 54)

Hemingway published his most groundbreaking work in the 1920s and 1930s. The next decades of his life were devoted to myth-making. In 1934, the high-society magazine Vanity Fair published a series of illustrations with the title “Vanity Fair’s Own Paper Dolls, No. 5: Ernest Hemingway, America’s Own Literary Cave Man; Hard-Drinking, Hard-Fighting, Hard-Loving—All for Art’s Sake” (Beegel, “Critical Reputation” 270; Blume). To view some of the paper dolls, see Lesley Blume’s “How Hemingway’s Bad Behavior Inspired a Generation.”

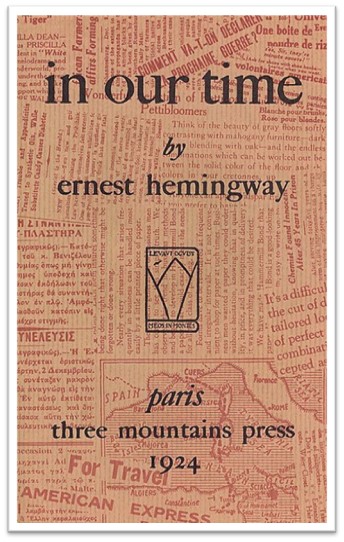

In Our Time

Like Winesburg, Ohio, Hemingway’s In Our Time is a short story cycle. Many of the stories deal with incidents in the life of Nick Adams, who is widely read as a stand-in for Hemingway himself. But In Our Time does not have Winesburg’s geographical centre, its nostalgic glow, or its appeals to poetry for wisdom or solace.

Hemingway wrote the untitled, italicized fragments before the longer stories. Many were based on wartime scenes Hemingway or his friends had lived through, either in World War I or the Greco-Turkish War that followed. The fragments were published in a thirty-one-page pamphlet called in our time (in lower case). The cover, a collage of newspaper columns in four different European languages, added to the impression of journalistic immediacy. “Our” time was ruptured by violence and dislocation; there was no time for reflection or adornment.

Let’s read the first interchapter (Chapter 1) together. “Champagne” was not a fine sparkling wine (drunk-talk notwithstanding) but a French military assault on Germany between September and December 1915. While considered a tactical victory for the French, it was devastating for both sides, with about 145,000 French and allied troops killed. Hemingway creates a sense of unease by juxtaposing the banality of the soldiers’ talk with ominous words such as “dark,” “dangerous,” and “the front” (Tetlow 19–20). In the last two sentences, we recognize that the passage is being narrated retrospectively. The speaker is no longer a kitchen corporal, a low-ranking position in which one would not be expected to participate in direct combat. What has happened to him? The episode is described as “funny” in hindsight for its incongruity with the horrors the men are about to see. Is the whole unit drunk because nothing is at stake? Or because everything is? This is a good question to ask of many of Hemingway’s characters.

Hemingway wrote fourteen longer stories over the following year, interspersing them among the fragments to create the first American edition of In Our Time (with capital letters). The setting of both “Indian Camp” and “The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife” was likely inspired by the woods around Walloon Lake in northern Michigan, where young Ernest’s family took

their summer vacations. Ernest’s father, Clarence, was a doctor who worked closely with the Ojibwe (also spelled Ojibway or Ojibwa) people of the region.

The Hemingway man enjoys controlled, purposeful violence: hunting, bullfighting, boxing, surgery. In “Indian Camp,” Nick’s father delivers a baby by Caesarean without proper equipment or anaesthetics. Nick’s father may be cold, but he is not cruel or uncaring. He tunes out the screams of the woman in labour, but sterilizes his knife and his hands thoroughly. Afterwards, the previously stoic doctor and his brother are “as excited and talkative as football players are in the dressing room after a game.”

But this is never the end of the story. Intruding upon the Hemingway man’s mastery of nature is some form of uncontrolled and incomprehensible violence. “Indian Camp” is the story of two “incisions,” one relating to birth and the other to death. A third incision into the experience of young Nick is implied: his childhood innocence is being cut open.

“Indian Camp” and “The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife” can be read as companion pieces. Both are dominated by silence and things unsaid. In the first story, Dr. Adams cleans his knife; in the second, he cleans his gun. But to what effect? In “Indian Camp,” Dr. Adams is in control; in “The Doctor,” his calm demeanour is shattered and his authority is undermined both by the Indigenous labourers and by his wife (who, as a Christian Scientist, likely discounts modern medicine). In “Indian Camp,” Nick turns to his father for refuge; in “The Doctor,” it is the reverse.

Before continuing, read “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.”

“The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber”

- To see more pictures of Hemingway in Africa, visit the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum’s “Hemingway Media Galleries.”

In 1934, while on safari in Tanganyika (modern-day Tanzania), Hemingway fell ill and had to be airlifted to safety. From that experience came Hemingway’s two “African stories,” “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” (not included here).

Hemingway’s world travels were part of his allure as a writer. “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” offers a trenchant critique of a certain type of American abroad—the “great American boy-men,” a type Hemingway himself had helped create.

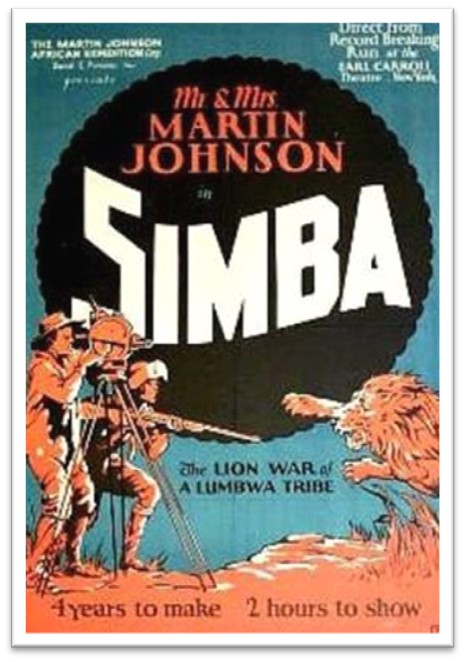

[A]s the society columnist put it, they were adding more than a spice of adventure to their much envied and ever-enduring Romance by a Safari in what was known as Darkest Africa until the Martin Johnsons lighted it up on so many silver screens where they were pursuing Old Simba the lion, the buffalo, Tembo the elephant and as well collecting specimens for the Museum of Natural History. (“The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber”)

“The Martin Johnsons” were Martin and Osa Johnson, an American couple who went on numerous African safaris and filmed their adventures. Hemingway’s use of italics and capital letters in this passage indicates a parodic tone: The Macombers are dupes who have purchased an exotic experience in the hope of reigniting their marriage. Wilson has seen it all before. At the same time, Macomber’s naïveté allows him to see things Wilson does not. Macomber, the American outsider, is uneasy when he learns that the African workers are poorly paid and disciplined by whipping; Wilson, the British colonist, does not care (DuCille).

Hemingway considered “Macomber” his crowning achievement as a short story writer. It compresses more adventure, psychological intrigue, and social observation than many writers could fit into a 300-page novel. Here is a characteristic Hemingway passage, seemingly simple but shot through with dramatic tension:

It was now about three o’clock in the morning and Francis Macomber, who had been asleep a little while after he had stopped thinking about the lion, wakened and then slept again, woke suddenly, frightened in a dream of the bloody-headed lion standing over him, and listening while his heart pounded, he realized that his wife was not in the other cot in the tent. He lay awake with that knowledge for two hours. At the end of that time his wife came into the tent, lifted her mosquito bar and crawled cozily into bed.

The source of the man’s suffering could have been captured in one simple sentence: “Francis Macomber…realized that his wife was not in the other cot in the tent.” But before we can reach the final clause, we must traverse series of rhythmic phrases that mimic Macomber’s pounding heart. Hemingway makes the sequence of subordinate clauses and the jagged rhythms of his phrasing evoke Macomber’s acute insecurity. The description is a series of precise events and images: the time moves from three o’clock to five o’clock in the morning; Macomber wakes, sleeps, sees a bloody-headed lion in a nightmare, lies awake; Margot comes into the tent and gets into bed. That is all. But Hemingway arranges the sequence of events and images to suggest a psychological trauma for Macomber and a marital relationship so damaged that one partner thrives on hurting the other.

At various points in his career, Hemingway compared his writing to an “iceberg”: what is told to the reader directly is only one-eighth of the story, and the rest lies below the surface (quoted in Strychacz 59). Hemingway eliminated all details that were irrelevant or decorative, and then went a step further: he omitted some important details.

For example, the significance of the seating arrangements in the car may not be apparent upon first reading. The passage in which Margot reaches forward from the back seat and kisses Wilson remains as a memorable dramatic incident. But, in fact, the drama depends not so much on the woman’s action as on the positions of the characters in relation to one another. When Macomber had first gone hunting, Hemingway had established his status in the group by describing his position in the car. Macomber has the preeminent favored position in the front; Wilson and Margot occupy the rear. When, after showing cowardice, Macomber is relegated to the back seat, Margot sits beside him. Her change of emotional commitment is shown by her leaning forward and kissing Wilson, her new image of heroic masculinity. Then, on the next day’s hunt, as Macomber begins to find his courage again, he sits forward on the rear seat. Margot, sensing a difference in him, eyes him strangely. As her husband’s courage grows, his fears overcome, Margot sits back “in the corner of the seat.” When Macomber leaves the vehicle and goes into the bush to confront the animal, she does not return his wave. Thus, Hemingway’s selection and arrangement of precise events (the iceberg’s top) makes implications about the changes in his protagonists’ emotions and motivations. The ultimate question of whether Margot intended to kill her husband is left unanswered. Hemingway’s use of implication and refusal of closure are examples of Modernist techniques aspiring to be more realistic than Realism.