16 Carl Van Vechten’s Heaven

Carl Van Vechten’s Heaven

Carl Van Vechten was a white, Iowa-born, openly gay (though married) critic and photographer who made his life in the New York art scene. If you see a photograph of any American Modernist, there’s a good chance it was a Van Vechten. Van Vechten was not alone in being interested in African and African American culture: Picasso, Stein, and Anderson were, too. But the extent of his interest was exceptional. He described himself as “violently interested in Negroes” (quoted in Ngai 178).

See Extravagant Crowd’s webpage “Nella Larsen” for a (still copyrighted) photo of Larsen by Van Vechten.

His 1926 novel N***** Heaven is a romp through a Harlem inhabited by writers, dancers, pimps, drug dealers, and a naked voodoo priestess. Its jazz lingo is evocative, if not exactly convincing (“Dawgonne, ef that ain’t the cat’s kanittans! … Bardacious!”). More importantly, this novel popularized the term “passing.” Van Vechten himself is rumoured to have passed as black for a period of his life. While thin on plot and characterization, the novel is full of ironies of mistaken racial identity, as in the conversation between Byron and Dick at the fictional Black Venus nightclub:

Hello yourself! cried Byron, grasping his friend’s hand. What in the world are you doing here?

Slumming. Brought some friends up with me. Come and sit with us. We’ve got plenty of gin.

I’d be glad to. I was wondering where I would sit. He hesitated before he inquired, Are you white or coloured tonight?

Buckra, of course. And so are my friends, but they’ll be delighted to meet you. They’ve heard about the New Negro! Dick grinned.

Dick is black. This evening, he is passing as “buckra,” using an African-derived slang term for a white person or a slave master, and trying to convince Byron he could do the same. For Byron, “wondering where [he] would sit” is about more than the choice of table: Most Harlem shows were for white audiences only, and even the few integrated nightclubs had segregated seating and bathrooms. Byron is asking himself what “mask” he would be willing to assume.

“Slumming” was both a type of tourism—going to a poor or seedy neighbourhood for thrills—and a literary subgenre that emerged in the late nineteenth century. As Scott Herring explains:

The formula for many of these [novels] was deceptively simple: a narrator inspires curiosity in his middle-class audience; tells it a story of startling revelation about urban classifications in cities such as Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Louisville, and New Orleans; and leaves said middle-class audience with what counts for knowledge about a criminal

underworld. (Herring 5)

Slumming texts, also called “city mysteries,” ranged in tone from lurid sensationalism to earnest appeals for social reform. As Herring says, the type of knowledge these texts promised was a set of “classifications”: the social hierarchies and stereotypes operating within a minority culture or subculture. Just as Dick uses the term “slumming” in a tongue-in-cheek way, N***** Heaven as a whole both participates in and parodies the slumming novel convention. At the end of the book is a glossary of “unusual Negro words and phrases,” which at once exaggerated the foreignness of black culture and mocked readers for expecting an authoritative guidebook. The entry for boody reads “See hootchie-pap,” and the entry for hootchie-pap reads “See boody” (Kathleen Pfeiffer, intro. to Van Vechten xxviii).

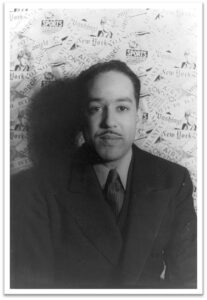

The allusion to Langston Hughes is not so much a parody of Hughes’s poetry as it is a jab at the white newspaper columnist Rusk Baldwin for dismissing Hughes as “a bus-boy or something.” Hughes did indeed work as a busboy. A lifetime friend of Van Vechten, he would eventually become one of the preeminent African American poets of the twentieth century. In the 1920s, when black poets were encouraged to write in traditional English forms such as the sonnet (thereby proving their “civilization” through the mastery of strict metres), Hughes infused his poetry with vernacular speech and the rhythms of blues and jazz music (Young). Van Vechten had a hand in bringing Hughes’s work to a major publisher, as he would later do for Larsen.

Several of Van Vechten’s black acquaintances urged him to scrap the book, or at least change its title. Du Bois said that it portrayed Harlem nightlife as a “barbaric drunken orgy” (quoted in Kaplan, intro. to Passing,xii-xiii). It didn’t help that gin, wine, and whiskey flowed freely in Van Vechten’s Harlem, even though alcohol was illegal during those Prohibition years. But others, including Larsen, admired Van Vechten’s work. As Kelefa Sanneh points out, the controversy around Van Vechten reflected a generational divide between writers who came of age in the nineteenth century and their younger, hipper counterparts.

A deeper reason for Larsen’s admiration of N***** Heaven was that Van Vechten recognized the contradictory nature of racial belonging. Like Passing, N***** Heaven sets up a contrast between a refined but uptight black woman and her sexier, more transgressive counterpart: Mary Love, a librarian (like Larsen, coincidentally), and Lasca Sartoris, modelled on singer-pianist Nora Holt. Sanneh writes:

[T]hroughout the novel, the character most obsessed with primal and exotic Negro identity is Mary, whose hunger for racial authenticity becomes a cruel running joke. ‘She admired all Negro characteristics and desired earnestly to possess them,’ we learn, though she also suspects that this desire is self-defeating. ‘Unless I acted naturally like the others, it would be no use,’ she thinks, and the novel turns on the question of what it might mean for a college-educated Negro to act ‘naturally’; this ongoing debate makes the novel much more interesting than its characters or its plot. (Sanneh)

As Emily Bernard observes, “To Larsen and others who supported the book, its greatest achievement was that it dramatized the paradox at the core of black American identity…which was that the line between blacks and whites was both fact and fiction” (Carl Van Vechten 149).

- To see some of the illustrations from a 1931 edition of Van Vechten’s novel, see the Museum of Modern Art’s “N***** Heaven (15 Illustrations from Carl Van Vechten’s Novel).”

- To see more of Van Vechten’s portraits (more than 3000 in total), see Yale University Library’s “Carl Van Vechten’s Portraits.”

- To see Hughes perform “The Weary Blues” with a jazz band for CBC Vancouver in 1958 (32 years after the poem was published), watch the video from Vanalogue, “Langston Hughes – ‘The Weary Blues’ on CBUT, 1958.”

Source: Youtube, vanalogue.

Before continuing, read Countée Cullen’s “Heritage”: first the lines Larsen used as the epigraph to Passing (p. 4), and then the poem in its entirety.

Countee Cullen’s Conversion

In the 1920s, many black writers were beginning to look to Africa as a source of tradition and pride. Langston Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” is one of the most striking expressions of pan-African identity by an American writer. A more radical vision came from the Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey, who argued that the only route to black emancipation was to return to Africa.

To many other black Americans, however, Africa was as foreign intellectually as it was geographically. This was the case for the New York University- and Harvard-educated poet Countee Cullen. The stanza from Cullen’s “Heritage” which Larsen used as the epigraph to Passing ends with the question, “What is Africa to me?”

Is that the statement Larsen is making: that the characters in Passing do not feel a sense of connection to their African ancestors? We can’t be sure. Whenever a writer uses an excerpt of a longer text as an epigraph, she is inviting the reader to consider the quoted text as a whole. (Here, Larsen may also be making a sly nod to N***** Heaven, which opened with a different epigraph from the same poem.) Even though Cullen’s speaker seems bemused by “Africa” in the lines Larsen quoted, the rest of the poem swoons with desire for a mythic African past.

“Heritage” reworks the Old Testament story of the Garden of Eden (Genesis 2–3). It is the speaker’s Christian upbringing that allows him to imagine Africa as Eden, with his foremothers as black Eves, but the same tradition tells him that God is white. His ancestors made “gods” (totemic objects) in their own likeness. Could he, then, make a black Christ? The speaker’s spiritual longings are interwoven with physical ones: after all, in Eden, Adam and Eve were naked and unashamed. Every night, the pounding of the rain stirs in him the “measures”—the

metre, or pulse—of “jungle boys and girls in love.”

Why is the speaker ashamed of these desires? As the Old Testament makes clear, no one can return to Eden. In the early twentieth century, words such as “jungle” and “primal” were part of the vocabulary of scientific racism (as discussed in our units on Frank Norris and Charlotte Perkins Gilman). The idea of a “natural rhythm” common to people of African descent was used by European writers to argue that black music was unsophisticated and animalistic. Some white critics worried that the “hot” rhythms of jazz would cause “hot blood,” leading to a frenzy of sex and violence (Radano; Golston). Before you laugh this off as a moral panic of the 1920s: Have you ever been warned about the “dangers” of rap music, or worried about what your kids were listening to? Cullen knew these images evoked racist stereotypes, but he turned to them nonetheless. The mythical idea of Africa held out the promise of wholeness after so many years of “play[ing] a double part.”

As you read Passing, ask yourself whether Larsen’s themes are better captured by the epigraph considered in isolation, or by the poem considered as a whole. As we said, there isn’t a definitive answer. Your answer might change depending on the character you focus on.