2 Art, Class, and Authenticity

Art, Class, and Authenticity

“The Real Thing” is a comedy of manners, a subgenre older than Realism in which the humorous exploration of social customs takes precedence over complex plotting or character development.

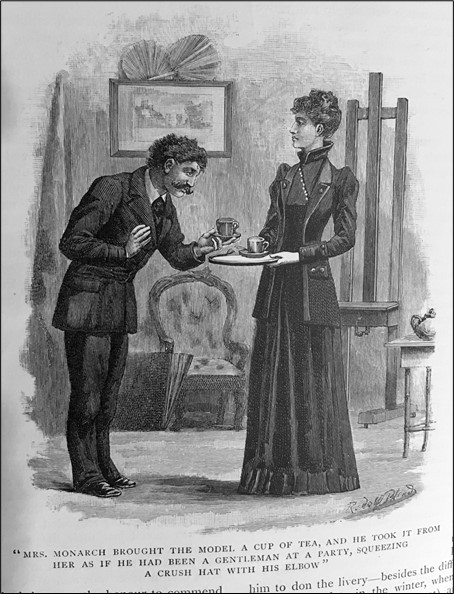

James sketched out his plan for “The Real Thing” in a journal entry from 1891 (in Tales of Henry James, 396–398). It began with a real-life story James heard from one of his friends, the London-based painter George Du Maurier, who was been approached by a retired general and his aristocratic wife who had ran out of money and asked if they could be his models. This anecdote inspired “The Real Thing” and what we’ll call Irony Number 1: Mr. and Mrs. Monarch are no good at pretending to be aristocrats because they are aristocrats.

Starting with this central irony, “The Real Thing” puts the assumptions of Realism to the test. Realist writers and Realist painters alike placed a high value on truthfulness. In “The Art of Fiction,” James asked an English novelist, whom he considered a “woman of genius,” how she had crafted her French Protestant characters with such precision. The novelist told him that she had simply walked past a dining room where a group of French youths were finishing a meal, and, as James put it, “The glimpse made a picture; it lasted only a moment, but that moment was experience. She had got her direct personal impression, and she turned out her type” (H. James 383; quoted in Monteiro 44). This is Irony Number 2: In order to write (or paint) convincing individuals, it was necessary to see individuals as members of types. In James’s words, it was necessary to look beyond the “literal” to see the “characteristic” (quoted in Monteiro 44).

“Types” also hint at the mechanical reproduction of images, and the way new technologies have impacted the painter’s understanding of his craft. For example, a stereotype was originally a metal plate used to make duplicate copies of a typeset page, and the daguerreotype was the first widely used photographic process. When the narrator compliments Miss Churm backhandedly by saying she has “no positive stamp” (ch. 3), he is alluding to these duplication processes.

Many Realists of the 1880s and 1890s regarded photography as an artless art form (e.g., Orvell). A photograph was a copy from a negative which absorbed light passively and indiscriminately. Of course, the photographer himself or herself is not passive. Photographers have been “lying” with camera angles and darkroom techniques since the mid nineteenth century. Nevertheless, for James and many others, the camera was an “amateur,” unable to spot the “illustrative notes,” patterns, and, yes, “types” within the raw materials of life. “The Real Thing” suggests that artists and models alike need to “learn to see” (ch. 4). The fact that this line is spoken by Jack Hawley, a bohemian with no talent of his own, is Irony Number 3.

Writers, too, could be “ridden by a type.” “The Real Thing” is as much about good and bad literature as it is about good and bad art. The narrator spends most of his time working on “stale properties—the stories I tried to produce pictures for without the exasperation of reading them” (ch. 1). He leaps at the chance to illustrate the collected works of “one of the writers of our day—the rarest of the novelists—who, long neglected by the multitudinous vulgar and dearly prized by the attentive” (ch. 2). One suspects that James was thinking of himself when he wrote those lines. James would later prepare a lavish “édition de luxe” of his own collected fiction—the twenty-four-volume New York Edition—between 1907 and 1909. The first volume of the New York Edition was his 1875 novel Roderick Hudson, the title of which sounds vaguely like “Rutland Ramsay,” the fictional book “The Real Thing’s” narrator hopes to illustrate.

In his decisions about where to publish his work, James was torn between a desire to reach as many readers as possible (the “multitudinous vulgar”) and a conviction that his work deserved sophisticated, “attentive” readers (e.g., McGurl). The narrator of “The Real Thing” sees himself as a member of the second category, but is he? As Adam Sonstegard points out, the artist “shows merely a passing attention to details and seldom checks his work against the written material he is supposed to be illustrating” (179). If you’re keeping count, this is Irony Number 4. The artist’s snobbishness about literature can be read as a form of “modelling,” enabling him to assume a high-class status without being wealthy.

At the beginning of “The Real Thing,” we learn that Claude Rivet had told Major and Mrs. Monarch

that I worked in black and white, for magazines, for story-books, for sketches of contemporary life, and consequently had frequent employment for models. These things were true, but it was not less true (I may confess it now—whether because the aspiration was to lead to everything or to nothing I leave the reader to guess), that I couldn’t get the honours, to say nothing of the emoluments, of a great painter of portraits out of my head. (ch. 1)

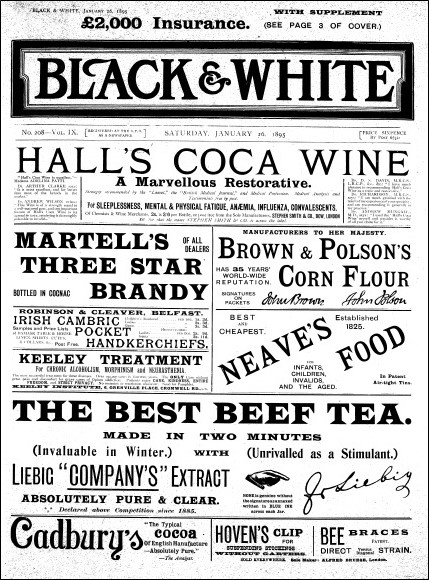

“I worked in black and white” may be a gentle jab at Black and White, the British magazine where the story first appeared. Black and White was a popular “middlebrow” magazine. Some of the best-known writers of the Victorian period were published in its pages, but top billing went to the illustrators (for an extended discussion, see Sonstegard). Unlike some older magazines that catered to a wealthier audience, Black and White did not disguise the fact that its revenue came from advertising inexpensive household items.

Make note of the contrast the narrator draws: Rivet, a landscape painter, has presented the narrator as a sketch artist, but the narrator thinks of himself as “a great painter of portraits.” What’s the difference? A sketch artist produces many images of anonymous people, which are mechanically reproduced, glanced at for a few seconds, and then thrown away. A “great” painter produces a small number of paintings of distinguished people, to be admired by a select few. But the narrator is not wealthy. He knows that being a “great painter” brings prestige, but it does not guarantee a living. The narrator still sees himself as too good for some projects. He would rather illustrate a trashy romance than an advertisement, and it appears that even the destitute Monarchs feel the same way.

William Dean Howells, the celebrated publisher of American Realism, may have observed that “the pride of caste is becoming the pride of taste,” but James’s fiction was saturated with class divisions (Howells, ch. 27). Miss Churm is marked by her accent, her large family, and her taste for beer as a “cockney” or working-class Londoner. Who is more pitiful: Miss Churm, who has to walk half a mile from the bus station, or the Monarchs, who “visibly wince” at the sight of her wet umbrella? Oronte is identified as a lazzarone, a man of the pauper class of Naples, Italy, who came to England because he could not make a living selling oranges by the side of the road. Finally, while the title Black and White has nothing to do with skin colour, the narrator’s remark about “useful blacks” (ch. 1) attests to the casual racism of genteel society.

For the artist’s models, dressing up and playing a character is a temporary escape from their social circumstance. This leads us to Irony Number 5, which we will leave to you to articulate. By the end of “The Real Thing,” some of the characters have remained true to “type,” and others have shown a capacity for change. Are they the ones you expect? In the end, does it matter?