11 Feminist Utopia in Herland (1915)

Feminist Utopia in Herland (1915)

Utopian dreams are to life what an architect’s plans are to a house—we may build it—if we can. Of course if he has planned wrongly—if the thing won’t stand, or does not suit our purpose, then we lay it aside and choose another. -Gilman, “A Woman’s Utopia” (1907) (Herland and Related Writings 204)

The purpose of this topic is to unpack the idea of utopia: in its relation to the travelogue genre and the emergent genre of science fiction; in relation to questions about narrative, individuality, and characterization; and in relation to radical social movements of the nineteenth century.

From the last pages of the introduction, make sure you understand the following:

- Gilman’s motivations for writing

- How Gilman was inspired by earlier utopian writings (p. 20): you may wish to

find a short summary of each online - Why Sutton-Ramspeck compares Herland

to an exemplum (a type of sermon)

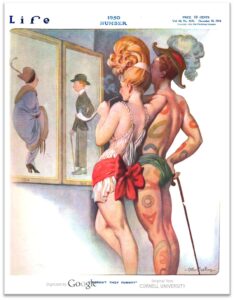

The magazine cover above represents what one artist in 1914 believed America might look like in 1950. What visual signifiers do you notice? What fears and/or desires is the artist expressing? How do you think Gilman would have responded?

Travelogue, Science Fiction, and Imperialism

From Sutton-Ramspeck’s introduction, you will have read about Herland’s debt to the travelogue genre. Many classic English novels have taken the form of a travelogue, in which a European protagonist’s adventures in a foreign land provoke critical reflections upon customs at home. Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) are famous examples. As well, many of the anthropological works Gilman studied were travel narratives. Early anthropologists commonly equated travelling through space with travelling through time; under the racist logic of the era, that meant travelling from a “civilized” present to a “primitive” past. Herland subverts this convention in several ways. The nation of Herland is literally newer than the civilization from which the men arrive, and the men are finally unable to assert that their civilization is the advanced one. And the Herlanders study their visitors as unsparingly as their visitors study them.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the U.S. was emerging on the stage as an imperial power, having recently acquired large swaths of Indigenous North American and Mexican territory, Puerto Rico, and (from 1898 to 1946) the Philippines. President Roosevelt linked the conquest of foreign lands with American manhood. But after centuries of British, French, and Spanish imperialism, there were very few uncharted regions for Europeans to “discover.” Herland’s Terry gives voice to this ideology when he complains that there was “nothing left to explore now, only patchwork and filling in” (ch.1).

The feeling on the part of white Americans and Europeans that there was “nothing left to explore” gave rise to the first wave of popular science fiction novels (Link and Canavan 8–9). These books were often premised on the discovery of an alien civilization which needed to be tamed, if not wiped out. If Herland is a science fiction novel (as it has been called since the 1980s), it reverses the conquest narrative. The women have made it their mission to “tame and train” the men (ch. 8; quoted in Salazar 152).

Utopian Experiments in America

Gilman was not the only thinker to envision a complete transformation of society. To learn about some of her forebears and fellow travellers, browse the exhibition “America and the Utopian Dream”. We recommend the following entries:

- Karl Marx, in the section called “Utopian Literature”

- Edward Bellamy, in the section called “Utopian Literature”

- “Transcendentalism and Fourierism”

- Oneida, in the section called “Utopian Communities”

- Icaria, in the section called “Utopian Communities”

- Kaweah, in the section called “Utopian Communities”

For each historical figure, consider the degree to which their attitudes toward the family structure, labour, sex, or scientific progress align with Gilman’s. How do you account for any differences in outlook? If you would like to delve into this topic further, selected primary texts are available at the Marxist Internet Archive’s “Utopian Socialism” (for the record, very few of the people in this tradition were Marxists). You will not be asked specific questions about these people or places on your exam.

Is Utopia Boring?

Compared with “The Yellow Wall-Paper” and McTeague, with their escalating tension and violent climaxes, Herland can feel slow-paced, even dull. Is this a fault of its author? A con-s quence of the novel’s having been published one chapter at a time over a period of twelve months? Or is it deliberate?

Consider the following analysis of Herland by scholar Cameron Awkward-Rich:

Plot is a problem for utopian fiction […]. If the utopia in question is truly an ideal place, then minimal conflict can occur. On the other hand, if the utopia is truly ‘no place,’ much of the textual work must go into its description. Either way, utopian fiction is, almost by necessity, largely a fiction of the mundane, the everyday, the cyclical. Many utopian writers solve this problem by introducing an outsider narrator who models the range of feelings produced in the encounter, from the open-mouthed astonishment of or longing sparked by the new world, to the fury, resentment, or laughter initiated by coming into conflict with the standards of one’s own world. Gilman, however, makes the desire for plot and adventure a thematic concern in Herland, since the desire for adventure is equated with a masculine desire for mastery and is therefore constantly denied to both the male explorers and to the reader. (Awkward-Rich 340)

Notably, it is the novel’s embodiment of the “masculine desire for mastery,” Terry, who grows bored with the books the women of Herland give him.

In her non-fiction book The Man-Made World: or, Our Androcentric Culture (1911), Gilman complained that much of Western literature was “restricted” to two main plots, the story of adventure and the love story. She argued that those plots were fundamentally masculine in their narrative structure, driven by conflict and “predatory excitement.” The conventional love story was nothing but “the Adventures of Him in Pursuit of Her—and it stops when he gets her!” (Gilman, Man-Made World, ch. 5; Awkward-Rich 339). Gilman was challenging the Western tradition’s most deeply engrained presuppositions about narrative, including the centrality of conflict, the need for a climax, and the mere expectation of interestingness. According to Gilman, a great writer of any gender should “refuse to be held longer to the rigid canons of an androcentric past,” and tell stories that reflected the changing conditions of women’s lives:

The humanizing of woman of itself opens five distinctly fresh fields of fiction: First the position of the young woman who is called upon to give up her ‘career’—her humanness—for marriage, and who objects to it; second, the middle-aged woman who at last discovers that her discontent is social starvation—that it is not more love that she wants, but more business in life: Third the interrelation of women with women—a thing we could never write about before because we never had it before: except in harems and convents: Fourth the inter-action between mothers and children; this not the eternal ‘mother and child,’ wherein the child is always a baby, but the long drama of personal relationship; the love and hope, the patience and power, the lasting joy and triumph, the slow eating disappointment which must never be owned to a living soul—here are grounds for novels that a million mothers and many million children would eagerly read: Fifth the new attitude of the full-grown woman who faces the demands of love with the high standards of conscious motherhood. (Gilman, Man-Made World, ch. 5)

Another mostly taken-for-granted assumption Gilman’s work challenges has to do with character development. From the late eighteenth century onward, there has been a trend among writers of fiction toward psychological realism, with main characters often praised for their “depth” or “roundness” (recalling our discussion of James in Unit 1). But there is little in the way of character development and no uncertainty about any character’s motivations in Herland. Those things might, in fact, be as out of place in Gilman’s utopia as war and hunger. When Van derides the American mother for being “wrapped up in her own pink bubble of fascinating babyhood” (ch. 6), we may hear the voice of a misogynist, but we should also hear Gilman herself—the Gilman who wrote, for instance, that kitchens should be made communal and anyone who had “peculiar tastes” in food ought to be shamed (Peyser 84).

Gilman’s dislike of “self-expression”—and, as Katherine Fusco has argued, her dislike of personality itself—puts her at odds with both literary Realism and political liberalism. Her anti-individualism even makes her an outlier among utopian socialists. Karl Marx, by contrast, had envisioned a communist society in which a person could “do one thing today and another tomorrow” without having his identity bound to any type of work (Marx and Engels 1.1.1.A). The “phalanstery,” a communal living arrangement proposed by philosopher Charles Fourier and dreamed about by nineteenth-century American radicals, was supposed to group individuals according to the subtle differences in their “passions,” including sexual preferences. But

whenever Gilman mentioned sexual desire, it was with contempt; she genuinely hoped humans would evolve beyond it. In this respect, Gilman’s ideal world bears a stronger resemblance to the “scientific management” movements of the early twentieth century (think Henry Ford’s factory lines) than to nineteenth-century utopianism.

Did Gilman really think it would work? We’re not sure. To Somel, the idea that a loving mother would want to raise her own children is as absurd as the idea that a mother should fix her children’s teeth by herself. (After McTeague, we hope you’re catching these dentistry references.) Do you think Somel is giving voice to Gilman’s sincerely held views in this passage? Or is the absurd analogy Gilman’s way of hinting that something is “off” about the country of Herland? What evidence would you provide to support your answer?